Iconoclassica

12 Aug. 2016 | Carlo V Castel – Gun Room – Monopoli (BA)

8 Nov. 2014 | Rava Palaces – Ravenna

25 Sept. 2014 | Ancient convent of St. Francis – Bagnacavallo (RA)

by Ilaria iboni – Daniele Torcellini

Catalog by CadeArt Editions

Event under the patronage of the Province of Ravenna, City of Ravenna and City of Bagnacavallo

Francesco Petrosillo

The power of images

“No eye can include all visions.

No eye can ever preclude the possibility of a further vision, the appearance of a new element.

No theory of the glance may ever be put forward as final, which is to say, put forward as that theory which is able to grasp the first and last glance”.

The interpretation of classical Italian renaissance iconography is by now sedimented in the collective imagination. The works of the great masters of the age have been reproduced and utilised for all kinds of communicative functions, from advertising to the most trite citation and the great visions of more or less contemporary artists. A well known example is the use of one of Leonardo’s best known works in a publicity spot for mineral water, but there are many others. There is a widespread use of well known images to represent and communicate clearly defined meanings (the more or less censurable uses will not be dealt with here) with regard to which we should consider the enormous power of transmitting information, ideas and thoughts that a represented subject may have, that automatic mechanism to which our eye is subjected daily. Or perhaps, as Ferrari wonders, “If everything arose from the engravings and images of the Lascaux Cave more than on the Ionic coasts and in the thought of being? If the articulation of thought were only a recoil of the opening up of the image?”.

In the past the main purpose of works was to carry out, on commission, a communicative and popularising function for political, religious and social ends, and this had to be easily and immediately understood by everyone. With time this has not lost its power of communication, indeed it has become stratified and fortified in the collective memory. No one fails to recognise at once a Crucifixion or the expulsion from Eden, though they may not be able to identify the artist. Immediate understanding of complex meanings through renaissance iconography has also led to numerous studies in different disciplines, but this extremely fascinating and apparently taken for granted mechanism – which is actually highly complex – may still be used to create various meanings and new images.

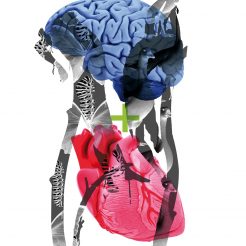

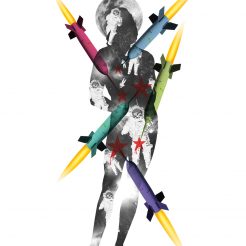

The artist’s creative process develops initially from identification of an old work, subsequently proceeding with selection of the significant detail which elicits the meaning and then beginning the contemporary proposal. The contemporary image is created at the moment of activation of the synthesis mechanism typical of the contemporary approach in which whatever we see, do, say or write will be inexorably synthesised to the limits of comprehension: examples of this are texting and the innumerable abbreviations rife in our everyday lives. In this sense there is an evident use of numerous symbols, a synthesis precisely, throughout the whole of Petrosillo’s oeuvre. The artist sets himself the problem of how an image was understood in the past and of how the same meaning could be represented now. How would an Annunciation be represented in 2014? Or again, a St Sebastian, does a vision of a man bound and struck by arrows currently exist? In reality, current events amply support the artist’s creativity. The element evoked by the old “sign”, by natural analogy, evokes an absent thing and in effect, ironically, the contemporary sign in certain cases reveals the object absent in the old work or, simply, highlights a detail or puts forward a meaning opposite to the old one; thus at this point the new meaning appears, the complete reading of the two propositions creates the new vision: the proposal.

Petrosillo renders symbols visible, meanings that are well known and present in everyday contemporary life, and inserts them critically – in the most specific sense of the term – as one who analyses and evaluates them, superimposed on historically codified iconographies. In fact the artistic process does not envisage another insertion into an already well known context or the transformation of a known subject but rather the selection of the signifier that maintains the past vision and, being overlaid on the contemporary element, permits interpretation of the new work. The syllogism comes about without ever losing sight of all the propositions, the work becomes a kind of 3D eyeglass capable of keeping its component elements visible while at the same time permitting a reading of the new narration.

In this case as in other works the artist takes the stance of one who puts forward possible points of view, rendered visible without defining a negative criticism of what he sees, but rendering visible current images, ways and thoughts in a manner that is ironic to the point of profanity. His action is not aimed at demythologizing renaissance iconography, indeed he strengthens its value by entrusting the old work with the power of communicating the meaning of the whole composition, which at the same time allows creation of the new meaning that emerges from the operation in itself but also from the superimposing of the two symbols: the contemporary work puts forward a renewed interest and curiosity in retracing and getting to know the original work that led to the composition of the new image.

Ilaria Siboni

The Empty Grouping. Towards a Pragmatics of the Image, Monza: Johan & Levi publisher, 2013.

Francesco Petrosillo, or on the alteration of memories

In the preface to his well known book Iconologia overo Descrittione Dell’imagini Universali cavate dall’Antichità et da altri luoghi Cesare Ripa, an academic and writer born in Perugia who lived astride the 16th and 17th centuries wrote: “Images made to signify something different than what is seen by the eye do not have any more certain or universal rule than the imitation of memories which are found in the Books, Medallions and carved Marbles produced by the Romans and Greeks, or by more antique peoples who were the inventors of this artifice. However it commonly appears that those who strive outside this imitation err, either from ignorance or over presumption, two faults much abhorred by those who with their own efforts seek to acquire praise. So to elude the suspicion of such blame I decided it was a worthwhile thing […] to deal with certain matters about the way of forming & stating symbolic concepts at the beginning of this work, which perhaps with too much diligence has been solicited by many friends who feel that I am obliged to satisfy them”.

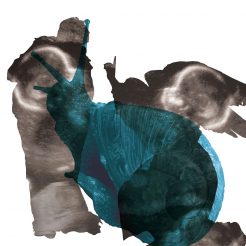

Francesco Petrosillo, cynical scrutinizer of reality that he is, in his latest project Iconoclassica seems precisely to set out from these premises, but with the explicit intention of upsetting if not actually subverting them. Petrosillo does his utmost in a deliberate sacking of classical forms, no longer to imitate but rather to corrupt the memories found in books, in medallions or marbles – as Ripa put it – in paintings in his case, in ongoing reinventions which stand astride recoveries of tradition and personal associations of ideas. His is a job of seeking symbols, sometimes to exploit, other times to empty out, in their conventional or codified meaning and in any case to reinterpret in unprecedented combinations which open up to sagacious, critical, bitter, ironic, acute and allusive conclusions, emblems no longer with mottoes one would say, on today’s society. But let us proceed in the right order.

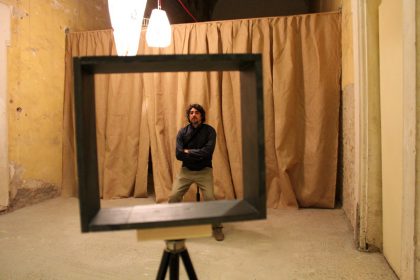

Francesco Petrosillo is a painter and graphic designer. The two things, which have never been interwoven in his activities, now find an avenue. The result is a hybrid which from the technical viewpoint could find a place under the label of digital painting, with all the risks connected with the superficial resistances which a medium, not new but certainly not yet clearly codified, could come up against in comparison with others far more established, as if photography in its day had not met with difficulties or as if the same hadn’t happened to video or cans of spray paint. Digital paintings behind which are concealed all the possibilities that the web, a great tank of images, sets at one’s disposal, but within which are also harboured the wide range of actions and transformations which a programme of image processing permits. Not least, the wealth that may derive from bringing together found images, created images and photographic images in one single digital operative space, for a mesh-up (in the IT sense of something that dynamically contains information and content from several sources) which is also a conceptual amalgam of those symbolic concepts so dear to Ripa.

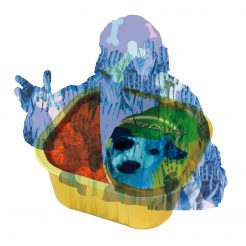

Thus the silhouette of Guido Reni’s Moses receiving the tablets of divine law becomes the background, pattern-filled with the black and white image of the no longer well known cathode ray tube television monoscope, of a simian profile which, thoughtful, is wearing an encephalic helmet, made of a monitor, topped by a satellite dish antenna. Perfect metaphor of a humanity – not fully evolved – which endures while striving to understand that which is administered by the media, be they digital, land or satellite. On an analogous theme the profile of the first of the magi from Bramantino’s adoration moves in a play of fingers and gestures of the hands, with the clenched fist of protest, the index finger pointing at Christ and the thumb pressing the remote control of the vintage TV screen which stands out inexorably above everything. An efficacious and light-hearted summary of our times, always poised between revival and urges towards the future, is the putto with scroll from Domenichino’s St Cecilia (patron saint of music), decorated with DJ mixer images and dancing figurines. Background of a light-blue audiocassette, it inevitably assumes the profile of a putto stereo boombox stand, in perfect eighties style.

The series dedicated to the deadly sins is compact and outstandingly emblematic: pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, sloth. The Archangel Michael, portrayed by painters famous and less so, intent on raining blows on the sinner par excellence, is a background to impersonal li- feless masks charged with objects that are symbolic or rendered symbolic by our artist’s inventions. Envy is outstanding, where the taste for citation and appropriation extends on multiple levels. In fact the mask takes on Hitler-like features, recalling the envy depicted by Otto Dix in the boy with squinting and diverging eyes, blond and ruffled but with a black toothbrush moustache. If lust, in sensuous shades of red, magenta and violet, could not but be embodied by the modern and well known symbol of the bunny with bowtie, greed is portrayed covered in dollars but crowned by what remains to most, an empty hand. The exhibition, which opens with the apple green of Masaccio’s expulsion from paradise which today, in times of crisis and difficulty, can only be an expulsion to paradise, finds its natural conclusion in the sin of pride of those who had the idea and the daring to pluck the apple, red and forbidden.

Daniele Torcellini

C. Ripa, Iconology, Turin: Einaudi publisher, 2012.