Magical Worlds

14 Jan. 2012 | Rava Palaces – Ravenna

03 Nov. 2011 | Port Authority – Ravenna

02 Sept. 2011 | Classense Library – Ravenna

by Ilaria Siboni

Text by Daniele Torcellini

Catalog by Danilo Montanari Editions

Event under the patronage of the Province and City of Ravenna

Mattia Battistini | Simone Gardini |

Pierpaolo Miccolis | Francesco Petrosillo |

Ettore Tripodi

Magical Worlds

“Luckily from somewhere, in a random and mysterious way, imagination leaps forth, the only guarantor of our freedom”. Luis Buñuel

Magical Worlds aims to inquire into certain contemporary painting practices that maintain the figurative idea while neglecting any realist approach. Five artists provide access to the same number of new fantastical, possible worlds, perhaps more real than what we consider such. The exhibition proposes an approach intended as freedom to tackle possible alternatives.

Magic is a controversial term. It has always had its upholders and those who are against everything it involves.

In every age and culture people have questioned themselves about its meaning and the place it may have in human life.

The need to investigate, as André Breton points out, represents the human characteristic of seeking the intervention of the extra-rational, and it is a theme dealt with in the fields of philosophy, religion and art.

Certain cultural, literary and artistic movements have based their thought on the imagination and the irrational element. In particular, as is well known, the surrealist view of the world comes about through the marvellous and astonishing. The Surrealist Movement developed from the original interpretation of De Chirico and Savinio who sought a completely free and anarchic vision of reality. Surrealism thus puts forward the idea of art of the imagination as anti-illusionist because it is linked to a capacity for vision beyond the commonly visible. Real, unreal and content of the work are especially fundamental themes in Savinio’s numerous writings; reality may be defined as the revealing of concealed aspects, meaning what the artist investigates, seeking to grasp the “fantastical” sense of things.

Magic is also an alternative to the already known, a different, unforeseen possibility that allows access to different realities and therefore to “freedom”. The content of the notion of magic is modified in accordance with the characteristics of the exponent and of the observer, which once more presupposes a broad margin of freedom. As Ernst Gombrich underscores, the human mind progresses through extension of interests and the understanding of more ancient ideas, which is to say passing from simpler to more complex ideas that are the continuation of previous ones and are the symbol thereof, understood as a sign of recognition. The symbol, an element employed to elicit an idea other than the immediately visible one, is utilised to evoke entities that are difficult to express. In the course of progressing, the human mind carries out an ongoing unmasking of foregoing symbols that are recognised as simple aspects or representations of truth. This is why magic is also the action engaged through the use of symbols, whose power is such that even when the content is imaginative the meaning is in any case recognised by the beholder.

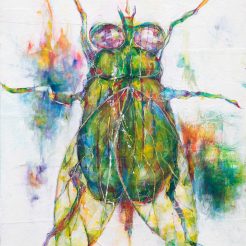

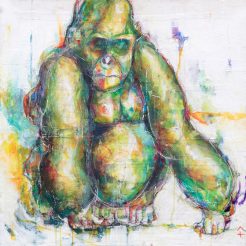

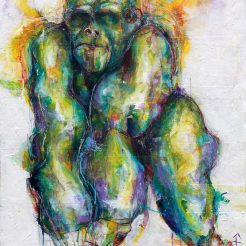

(…) The freedom to see and choose other places appears in the magical worlds of Francesco Petrosillo, always inhabited by animals. Animals have been part of the collective imagination right from our origins. In fact together with humans they represented the centre of the known. As John Berger underlines in “Ways of Seeing”, the close man-animal link represented economic and productive needs, but also magical, divinatory and sacrificial ones.

The economic development of the “western world” created a great distance between man and animal, nature, the primordial imagination. The great animals and insects with their vivid and absolutely unreal colours become the protagonists of the artist’s personal spaces. Animals return as an original reference of man, the first parameter of comparison that allows man to “distinguish himself as he distinguished them – that is, to use the diversity of species as a conceptual base for social differentiation”, Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Several years ago Petrosillo decided to relate to animals, or in any case to living beings that seem to exclude humans, in search of a new and pleasing world in which to recover simplicity and purity.

Representation of the various aspects of reality or unreality also renders visible the aspect of the monstrously painful, thus underlining the difference between barbarian and civilised. So we repeat one of the main features of artistic research in all epochs, meaning rediscovery of the uncontaminated eye of our origins. When such research succeeds in eliciting the emergence of aboriginal essence, what appears is the anguish produced between society and the most interior part of man. Numerous contemporary writings,

such as Aldo Carotenuto’s, deal with this question. (…)

The control of colour

Control of the forces of nature is the field in which magic exercises its widest range of possibilities, through esoteric and obscure practices and forms of knowledge that are to a greater or lesser extent irrational.

A matter of anthropological flavour in which man, the magician, the initiated, is capable of expressing his will to dominate natural but also supernatural forces and bend them to the most varied purposes. The “Magical Worlds” evoked by the artists in this exhibition – Mattia Battistini, Simone Gardini, Pierpaolo Miccolis, Francesco Petrosillo and Ettore Tripodi – are worlds where ineffable acts of magic have altered, distorted, manipulated natural logics, beaten tracks and consolidated appearances.

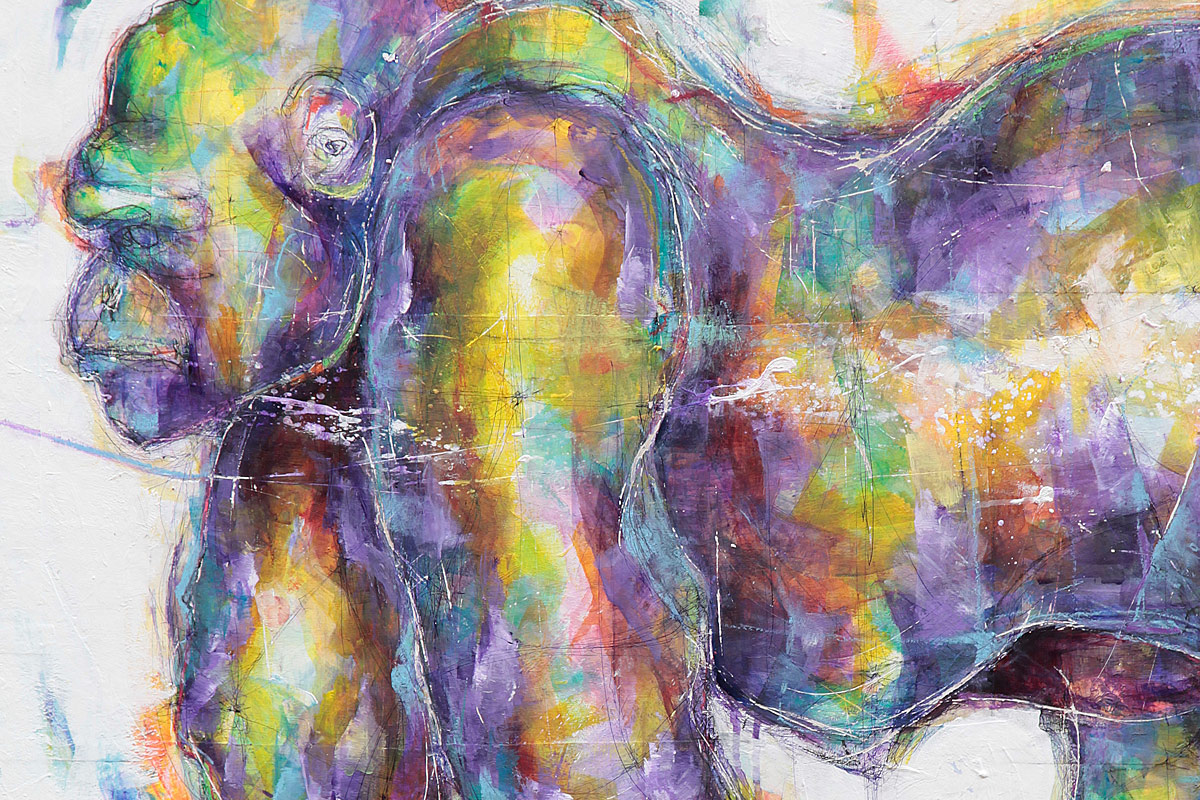

A link may be made between magic and colour, each in itself being indefinite, fleeting and enigmatic. Colour is an aspect of the real which lends itself less than others to definitions that are simple and shared: colour is uncertain, mutable, subjective, relative to context of observation, to light, to movement, to time. Colour deforms the world. Modern neurophysiology says that we are all equipped with a cerebral processing centre that deals with making us perceive as constant, within certain limits, colours which are actually always changing. A refined operation that struggles desperately against the variability of perceptual conditions. An imperfect system however, and one that does not assure stable communicative correspondence between man and nature. But this is only the rational side. Side by side with form – and the works on show have a curious sampling of monsters – colour is one feature which very often undergoes alteration in worlds where magic has produced its effects; almost as if its very lack of clear definition might make it the weak link in the chain of the real; the first to break in the case of magical manifestations or oneiric dimensions.

Shifts of meaning, anti-realistic mutations, increased perceptive evidence, destabilising estrangements, symbolic insistences.

The white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, Dorothy’s slippers in The Wizard of Oz, silver in the book and ruby red in the 1939 technicolor film. The contrasting and expressionist backgrounds of Mattia Battistini’s heraldic and hieratic figures. The colours of figurative worlds in which Simone Gardini’s micro narrations are immersed. The delicately leaden skies that supply a backdrop to the unnatural and violated creatures of Pierpaolo Miccolis. The violet yellow, blue orange modelled plastics of Francesco Petrosillo’s archetypical gorillas. The adimensional and gaudy golds and reds of Ettore Tripodi’s chivalrous narrations.

The painter, like the magician, must control and lay down colours, indefinite, fleeting and enigmatic, with view to inducing them to express his will.